Takeaways from Howard Marks: How to Think About Risk

Risk is a central concept in investing, and no one articulates its nuances better than Howard Marks, co-founder of Oaktree Capital.

I stumbled upon a YouTube video by Oaktree Capital in which Howard Marks explains risk from his perspective. Some of the points he made were similar to those in his book "The Most Important Thing." However, in this approximately 30-minute video (link attached at the end), he was more direct and simple in his explanation. So, I'm thinking of writing a summary of this video in my Substack. Here are my takeaways:

1. Risk Is Not Volatility

One of the most critical distinctions Marks makes is that risk is not equivalent to volatility. While many in the academic world, particularly those influenced by Modern Portfolio Theory, define risk as price fluctuations (volatility), Marks rejects this. According to him, volatility is simply a characteristic of the market — a symptom, not the disease itself. True risk, Marks argues, is the probability of permanent loss of capital.

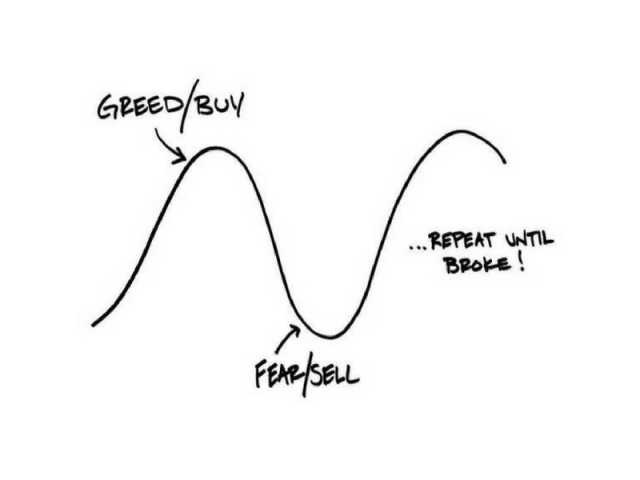

Volatility may cause temporary discomfort, but it doesn't equate to risk unless you sell at the bottom. As long as you hold your position, volatility can be weathered. For Marks, the danger lies in the investor’s response to volatility — often leading to panic selling during downturns — rather than volatility itself.

Volatility can be an indicator of the presence of risk, but it is not risk itself.

- Howard Marks

Based on Mark's explanation, it's important to understand that risk and volatility are not the same thing. Volatility is just an indicator of risk, not risk itself. I've noticed some investment professionals using the VIX to explain higher risk in the current market, but I strongly disagree with that view. While the VIX measures expected stock market volatility over the next 30 days, it doesn't provide a reliable measure of market risk.

2. Risk Is the Probability of Loss

Even when you know the probabilities, that does not mean you know what is going to happen.

- Howard Marks

Marks shifts the focus from volatility to the probability of loss, which he believes is the genuine essence of risk. Risk is the potential for an investment to result in a permanent loss of capital. Investors should demand compensation for bearing risk, not because the asset is volatile, but because it might lose value over time.

This understanding helps investors focus on the most important question: "How much could I lose if things go wrong?" rather than simply worrying about price fluctuations.

He provided an example from a game of backgammon. When rolling a dice, there are limited possible combinations, and we know the probability of the dice resulting in a sum of 7, which is the most likely outcome (16.7% probability). With a result of 6, there are 5 possibilities, and to get a sum of 2, there are only two possibilities. Therefore, we have a clear understanding of the probabilities of distribution, both likely and unlikely. However, knowing the probabilities does not eliminate the risk.

3. Risk Is Not Quantifiable in Advance (or Even in Hindsight)

This one is interesting for me. I have been working and researching on how to quantify risk in my portfolio but have not found the right method to come up with the right measurement. Howard Marks is super clear in his stance about quantifying risk.

Risk is not quantifiable.

Another insight from Marks is that risk cannot be quantified precisely in advance. Many investors and institutions try to assign specific probabilities to future outcomes, assuming they can predict risk with certainty. Marks argues that this is a fallacy, given that risk pertains to the future, which is inherently unpredictable.

Even after an investment is made and an outcome is realized, it’s impossible to quantify how much risk was involved retrospectively. For example, if an investment doubled in value, it doesn’t mean it wasn’t risky. The investor might have simply gotten lucky. Similarly, a loss doesn't necessarily indicate a risky decision; it could just be bad luck. The outcome, whether positive or negative, does not define the level of risk.

I remember an exercise I did in my grad school classroom at Columbia. We discussed the concept of talent versus luck in the stock-picking abilities of investment professionals. The only way we could measure someone's talent and luck was through simulation. However, the results are bounded and must be predetermined. Based on my own experience and what I learned from Marks, we cannot quantify risk.

4. Asymmetry: Seeking Positive Skewness in Returns

One of Marks’ most powerful ideas is the concept of "asymmetry" in investing. He believes that skilled investors should aim for asymmetrical outcomes — where they achieve better-than-market returns in good times and suffer less-than-market losses in bad times. This concept of positive asymmetry is crucial because it emphasizes the ability to outperform during bullish periods without experiencing proportionate losses during downturns.

This goes beyond merely generating high returns. An investor who produces a 20% return when the market is up by 10% and loses 20% when the market is down by 10% is simply taking excessive risk. True skill lies in minimizing losses while capturing most of the gains.

5. The Cardinal Sin of Investing: Selling at the Bottom

For Marks, one of the gravest mistakes an investor can make is being forced to sell at the bottom of a market cycle.

When prices decline, many investors panic and sell, locking in losses and missing out on the recovery. Marks emphasizes that this mistake is far more detrimental than buying at a high price and seeing a temporary decline. Why? Because markets tend to recover over time, and if an investor can hold on, the next high is often higher than the last one. The true risk lies in being forced out at the wrong time and unable to participate in the rebound.

6. The "Risk of Missing Out" and "Risk of Not Taking Enough Risk"

In addition to the classic view of risk as the possibility of loss, Marks also highlights a more subtle risk: the risk of missing out on opportunities. Investors who are too conservative may avoid losses, but they also risk not taking enough risk, which can lead to underperformance in a rising market.

This creates a balancing act: taking enough risk to capture upside potential while avoiding the kind of risk that could result in significant losses. Investors must weigh the risks of being overly aggressive against the risks of being too conservative and missing out on gains.

I understand that this may seem simple, and anyone with experience in the investing world is familiar with this dilemma. However, many people tend to be drawn more towards one side than the other. We are all familiar with the term FOMO, and many have fallen victim to this behavior during the recent bull market in crypto, tech investments, and other areas. Although the industry as a whole continues to thrive, the performance of VC investments has become less appealing than it was before. Therefore, finding a balance is crucial and requires a lot of mental effort, not just analytical work.

7. More Things Can Happen Than Will Happen

One of Marks’ most philosophical reflections on risk is based on the idea that “more things can happen than will happen.” In other words, the future is a set of possibilities, not certainties. The range of potential outcomes is broad, but only one outcome will occur.

This understanding forces investors to respect the uncertainty of the future. Even when probabilities are calculated, the most likely outcome is not guaranteed.

This mindset underscores the importance of humility in investing.

It’s not about predicting the future with certainty but about preparing for a range of possible outcomes and managing risk accordingly. So, the question that we should always try answering is: Would I be ready if I underperform the market? Would I be ready if my portfolio returns below the S&P500? If the answer is yes, then you are a step closer to understanding the risks in your investing process.

In line with his view that “more things can happen than will happen,” Marks highlights the importance of tail risks — the unlikely but impactful events that can disrupt markets. While most financial history occurs within a predictable range of outcomes, the most significant, memorable events tend to happen outside of these bounds. Marks refers to these as “wild cards” or tail events, and they are the moments when true risk is revealed.

8. Risk is Counterintuitive and Pervasive

One of the central themes in Marks' teachings is that risk is often invisible until it materializes as loss.

Marks illustrates this with a powerful example: The Drachten experiment.

In the early 2000s, the small Dutch town of Drachten, with a population of about 50,000, became the site of a radical traffic experiment led by traffic engineer Hans Monderman.

The core idea behind the experiment was counterintuitive: by removing traffic lights, signs, and road markings, drivers would become more cautious and attentive, leading to safer roads and smoother traffic flow.

Nearly all traffic lights were removed from Drachten's streets.

Out of 15 sets of traffic lights in the town, only 3 remained, with plans to remove those as well. In addition to traffic lights, other elements like speed limit signs, no-parking signs, curbs, speed bumps, warning signs, railings, and road markings were also removed.

The Results:

The outcomes of this experiment were surprisingly positive:

Safety Improvement: Before the experiment, there was typically one road death every three years. After the removal of traffic lights began, there were no road deaths for at least seven years.

Traffic Flow: The main junction in Drachten, which handles about 22,000 cars daily, saw a significant reduction in traffic congestion. Tailbacks became almost unheard of, and horn honking decreased dramatically.

This phenomenon highlights how risk is not inherent in the activity but lies in how participants approach it.

Similarly, in markets, perceived safety can lead to riskier behaviors. Investors may believe that low volatility or a booming market is safe, encouraging them to take on excessive risk. But, as Marks says, “Risk is high when investors behave imprudently.” The irony is that periods of calm and confidence often breed the most dangerous environments. The belief that there is little risk creates a perverse outcome: people behave more recklessly, thus increasing actual risk.

9 Risk is Subjective and Hidden

Marks argues that risk is deeply subjective, defying attempts to quantify it purely through historical data or models. He points out that most investors mistakenly equate risk with past volatility, a backward-looking metric that fails to capture the true uncertainty of the future. He prefers to think of risk as "the possibility of loss when negative events occur," and the true nature of risk only reveals itself when tested by adverse conditions.

Marks frequently references Warren Buffett's famous quote, "It's only when the tide goes out that you discover who's been swimming naked." Similarly, when markets are booming, risks are often hidden, giving investors a false sense of security. It’s only when a market correction or economic downturn occurs that the flaws in investment strategies are exposed, and losses are realized.

10. It’s Not What You Buy, But What You Pay

One of Marks’ most powerful insights is that risk is not a function of asset quality but of price.

High-quality assets can become risky when overpriced, while low-quality assets can be safe if purchased at a discount. This idea contradicts the traditional notion that “good” assets are always safe and “bad” assets are always risky.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, investors piled into the so-called "Nifty Fifty" stocks—considered to be the best and fastest-growing companies in America. Investors believed that these companies were so robust that no price was too high to pay. Yet, as Marks recounts, many of these stocks experienced sharp declines, with some losing over 90% of their value. The perceived safety of these high-quality companies had led to excessive prices, creating significant risk.

Conversely, when Marks started investing in high-yield bonds in the late 1970s, he found that these low-quality, risky assets could offer attractive returns when purchased at a discount. The lesson is clear: risk is a function of price, not the intrinsic quality of the asset.

11. Risk and Return: A Nuanced Relationship

Marks takes issue with the simplistic view that higher risk automatically leads to higher returns. This notion is prevalent in modern finance, where risk and return are often depicted as moving together in a linear fashion. According to Marks, this misunderstanding leads many investors to believe that taking on more risk will inevitably lead to greater rewards. In reality, riskier assets merely offer the potential for higher returns, but they do not guarantee them. The actual outcome could range from substantial gain to catastrophic loss.

To illustrate this point, Marks presents his own version of the classic risk-return chart.

Instead of a straight upward-sloping line, he uses bell-shaped probability distributions to represent the range of outcomes. As you move to riskier assets, the expected return may increase, but so does the range of possible outcomes, especially on the downside. In short, the potential for extreme losses grows alongside the potential for high returns.

12. The Importance of Risk Control

In Marks’ view, risk control is essential to investment success. However, risk management should not be sporadic or reactive; it must be a constant part of the investment process. Marks likens investing to soccer (and I guess this is the reason they injected USD 428M to Inter Milan) than American football.

In football, there are clear moments when teams switch between offense and defense. In soccer, the same players are on the field for both offense and defense, constantly shifting between the two as the game evolves. Similarly, in investing, there is no clear moment when you should switch from offense (seeking returns) to defense (managing risk). Both must happen simultaneously and continuously.

Marks also emphasizes that risk management is not about avoiding all risk, but about intelligently bearing the risks that offer the best reward potential. He likens this to buying insurance: you don't regret having car insurance even if you don't get into an accident. The value of insurance lies in the peace of mind it provides, not in whether or not an accident occurs. Likewise, prudent risk management helps protect against unexpected losses, even when times are good.

Conclusion: Embrace the Complexity of Risk

In the world of investing, risk is unavoidable, but its complexity is often misunderstood. Howard Marks’ perspective on risk highlights the need for investors to think beyond traditional metrics like volatility or asset quality. Risk is influenced by investor behavior, market conditions, and, most importantly, the price paid for assets. Understanding these nuances allows investors to navigate uncertain markets with greater confidence.

Risk is not inherently bad, but it must be approached with caution and intelligence. By acknowledging the subjectivity of risk, maintaining constant vigilance, and exercising discipline in pricing, investors can increase their odds of success and avoid the perils of complacency in seemingly "safe" environments. As Marks aptly puts it,

Investment success doesn’t come from buying good things, but from buying things well.

Source:

A master class in risk-taking!

Yes this was a great video!!