Buffett & Munger's Investment Commandments: Thou Shalt Not Commit These 8 Sins

We delve into 8 common investment pitfalls, highlighting the importance of avoiding emotional attachment, market timing, overreliance on projections, excessive leverage, confirmation bias, and more.

I was intrigued when the market fell nearly 3% due to the impact of the Japanese yen carry trade. This event was unusual, and not many retail investors could have anticipated it. That day, the Nasdaq was down by approximately 2.5%, and the S&P 500 was down by about 2.8%. This led to a significant spike in the VIX index, reaching its third-highest level since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the COVID-19 pandemic.

What was particularly intriguing for me was how retail investors responded to this situation. Many news channels, including CNBC, aired special reports about the turmoil in the markets. While I don't think this represents a consensus view, it at least reflects what CNBC (or people in general) perceived of the market at that time and it did not look good.

However, as many great investors, including Warren Buffett, once said,

"It's wise for investors to be fearful when others are greedy and to be greedy only when others are fearful."

I found this wisdom to be very impactful as I contemplated my next steps. Despite the market's instability, I was ready to take a risk and seek out more affordable stocks to invest in. This situation brought to mind Warren Buffett's thoughts on investment pitfalls (not in any particular order), which is what I'd like to discuss in this post.

1. Getting Emotionally Attached to Purchase Price

It is common for investors to become emotionally attached to their investments, and even the great Warren Buffett is not immune to this. When this happens, investors may become biased in their view of the future performance of their stocks and struggle to decide when it's the right time to sell. They often see things positively when the reality may be different, and they may overlook warning signs. However, in the long run, the true performance of a company is reflected in the market, and there's little investors can do to avoid losses except by selling early. Buffett made this mistake when Berkshire invested in Tesco in 2006, showing that even he is not immune to this.

Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway first invested in Tesco in 2006. At that time, Tesco was expanding rapidly in the UK and globally, with plans to open a new chain in the US. Buffett's initial stake was modest but grew steadily over the years. By 2012, Berkshire Hathaway owned more than 5% of Tesco, making it one of the company's largest shareholders.

By 2013, it became apparent that something was wrong with Tesco. The company faced declining sales due to increased competition from discount retailers like Aldi and Lidl, as well as high-end offerings from Marks & Spencer and Waitrose. Tesco issued four shock profit warnings between 2013 and 2014, indicating a significant downturn in the company's financial health. In September 2014, Tesco revealed an accounting scandal where it had overstated its expected half-year profits by £250 million. This revelation led to a full-scale investigation by the UK's financial regulator.

However, despite these troubling signs, Warren Buffett delayed selling his stake in Tesco. This delay proved costly as the company's problems worsened month by month. The after-tax loss from this investment was $444 million (approximately £287.6 million), which is about 1/5 of 1% of Berkshire's net worth. This loss was attributed to Buffett's "thumb-sucking," a term used by Charlie Munger to describe dawdling or procrastination in making decisions. In his annual letter to shareholders, Buffett admitted that he made a huge mistake by investing in Tesco and that he should have sold the shares earlier.

2. Trying to Time the Market

"When investing, we view ourselves as business analysts, not as market analysts, not as macroeconomic analysts, and not even as security analysts." (From the 1987 Shareholder Letter)No one can time the market, not even the savviest investors (or some people would call them hedge funds). Thinking that it's possible to time the market is like believing in a crystal ball that can predict which stocks to buy. In reality, there's no such thing as a crystal ball, and anyone who could do it would likely be one of the richest people in the world (and if people tell you the otherwise, they are lying). To illustrate how difficult it is to time the market, we can refer to the famous dispute between Buffett and Protege Partners.

Warren Buffett made a famous $1 million bet in 2007 regarding the debate between "time versus timing". He challenged the hedge fund industry by claiming that a simple S&P 500 Index fund would perform better than the active stock selection of hedge fund managers over a 10-year period. Protégé Partners accepted the bet, and over the next decade, they competed against the power of passive investing.

Ultimately, the hedge fund conceded, having achieved a return of $220,000 compared to the S&P 500 Index fund's $854,000. While Protégé did make a positive return, it was significantly smaller than the broader market's return.

3. Falling for Aggressive Growth Projections

It's important to remember that numbers alone cannot tell the whole story. As investors, it's our job to thoroughly analyze a company's performance and estimate the true value of an opportunity. Relying solely on an investment story could lead to a bleak reality. Therefore, investors should approach growth projections with skepticism and focus on sustainable growth. To explain this pitfall, there's Warren Buffet's investment in Dexter Shoe Company, which he deemed a dumb decision on his part. However, it still offers valuable lessons to be learned.

In 1993, Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway purchased Dexter Shoe Company, which later became known as one of his worst deals. Upon reflection, Buffett admitted to making more than one big mistake in buying Dexter Shoe Company.

The first mistake was a miscalculation about Dexter's prospects. Berkshire bought Dexter because of its high return on capital employed but failed to account for the company's competitive threat from cheap shoes from countries like China.

By 1999, Buffett noted that domestic producers were struggling to compete effectively in the shoe business, as approximately 93% of the 1.3 billion pairs of shoes purchased in the United States came from abroad. This highlighted the importance of checking a company's durable competitive advantage before investing in it, as durable competitiveness is no longer a good-to-have factor but a must-have factor for any business.

Buffett's second mistake was not purchasing Dexter Shoe Company with cash but using $433 million worth of Berkshire Hathaway stock. In 1993, one share of Berkshire's Class A stock was around $15,000, but today it is valued at $517,000. This decision cost Berkshire shareholders a princely sum of $15 billion for a company that ultimately became worth nothing.

4. Blindly Following the Herd

Buying a stock simply because everyone else is doing it can lead to irrational exuberance and painful losses. Investors should think independently and avoid emotional contagion in the market. This is not the story of Warren Buffett following the herd; it is completely reversed. Warren Buffett invested in a Chinese EV car company called BYD at the time the market was highly valuing Tesla.

Warren Buffett has a history of making contrarian investments, often going against prevailing market sentiment.

During the 1963 "salad oil scandal," he invested in American Express, recognizing its underlying value amid a crisis.

In 1976, he bought into GEICO when it was near bankruptcy, seeing its potential despite widespread skepticism.

During the 2008 financial crisis, he made a bold $5 billion investment in Bank of America when many investors were avoiding bank stocks.

More recently, Buffett has made substantial investments in Apple, Bank of America, and Chevron. In 2024, he further increased Berkshire Hathaway's holdings in Occidental Petroleum and Chevron, demonstrating confidence in the energy sector's long-term prospects despite market uncertainties.

In essence, Buffett's investment philosophy can be summarized as finding value where others see risk or uncertainty, demonstrating a willingness to go against the crowd and a focus on long-term potential over short-term fluctuations.

At the end of the day, it is not really rewarding to have a herd mentality. At best, you could only get average returns on your investment. While it is more challenging, having contrarian views increases your chances of beating the market and making your analysis useful.

5. Using Excessive Leverage

Using borrowed money can amplify returns but it is super risky and can lead to significant losses. While it is not uncommon to use leverage when it comes to project finance or LBO, parties involved should have a perfect understanding on how leverage could be returned to lenders and how much buffer (i.e., interest coverage ratio) a project or corporate could achieve. Because the majority of investors are retail who might not have time to take into account the risk in investing, it is much safer to invest with cold money than with hot money.

“My partner Charlie says there is only three ways a smart person can go broke: liquor, ladies, and leverage. Now the truth is, the first two he just added because they started with ‘L’ – It’s leverage.” Warren Buffett

6. Succumbing to Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias occurs when investors seek out information that confirms their initial thesis while ignoring contradictory evidence. Warren Buffett and his partner Charlie Munger actively combat this by seeking dissenting opinions and challenging their assumptions. However, in one instance, Buffett succumbed to this bias when he invested in Berkshire Hathaway in 1962. Despite making this mistake, Buffett acknowledged it and learned from the wisdom of Charlie Munger to alter his investing approach. Eventually, he always sought out advice from Mr. Munger.

It might come as a surprise. But Warren Buffett’s biggest investing mistake was purchasing Berkshire Hathaway in 1962. At that time, Berkshire Hathaway was a failing textile business. Nevertheless, it qualified under the classical Benjamin Graham model of identifying the cigar-butt business.

This favorable financial evaluation got a young Warren Buffett interested in the company. And he started buying the stock in tranches. Then in 1964, the owner of the firm, Seabury Stanton, offered to buy out Buffett’s shares at 11 dollars and 50 cents. Buffett agreed to it.

But when the offer letter came in, the offer price was down to 11 dollars and 32 cents. It infuriated Buffett. He purchased a controlling stake in Berkshire Hathaway. and then fired Stanton from the company.

While Buffett got his revenge, he was left holding a significant investment in a failing business. Until this day, Buffett remarks that it was the dumbest stock that he ever bought.

Buffett carried the burden of a failing textile business for 20 additional years. He admits that if he had included the cash flows of other businesses, like insurance companies, Berkshire would have been twice what it is now.

By his calculations, Buffett’s purchase of Berkshire Hathaway was a mistake worth USD 200 billion. The lesson here is that being emotional does not help with investing.

7. Buying a Stock That Loses Money

Buying a stock that loses money is considered a sin of commission, which refers to mistakes made during the investment process. This can result in significant financial losses.

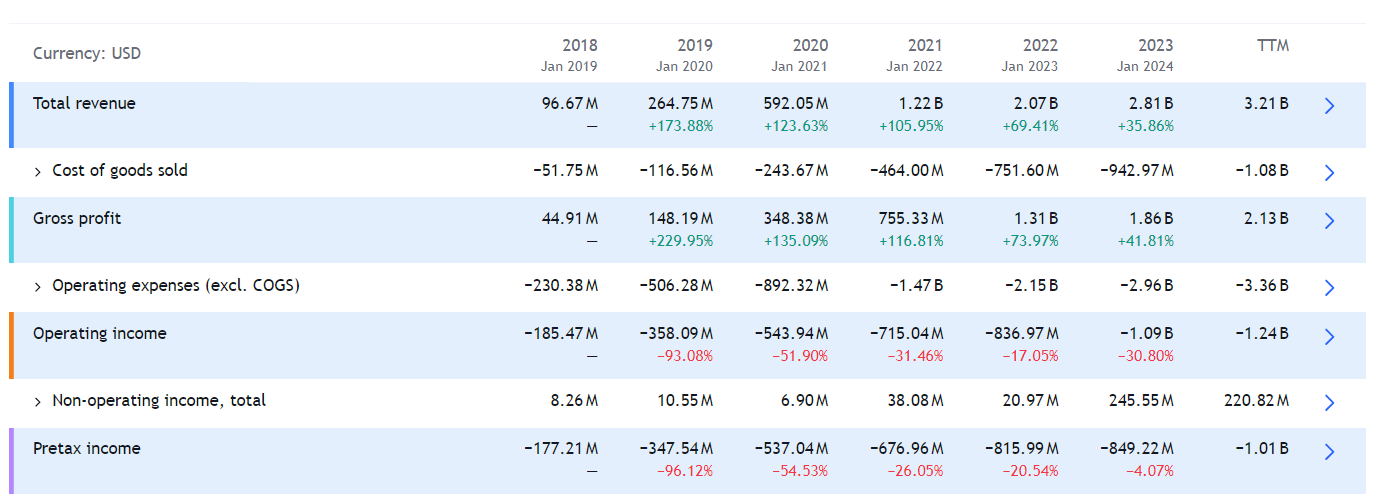

Berkshire Hathaway's investment in Snowflake, a cloud-based data company, was a notable move by Warren Buffett's conglomerate. Berkshire Hathaway invested in Snowflake during its initial public offering (IPO) in September 2020. This was a rare instance of Buffett purchasing shares during an IPO, reflecting his trust in the company's leadership and potential for growth.

Berkshire bought Snowflake stock at a pre-IPO price of $120 per share, which was a fantastic deal since the stock began trading at around $245 that day. Although Snowflake stock traded for an average of $148 in Q2, there were two ranges: before and after Q1 earnings were released on May 22. If Berkshire sold before earnings, it likely got around $155 per share; if it sold after, it was probably around $125.

The investment was influenced by Todd Combs, one of Buffett's associates, who had a professional relationship with Snowflake’s former CEO, Frank Slootman, through his role at Geico. This connection aligned with Buffett's preference for investing in companies led by individuals he trusts.

By the second quarter of 2024, Snowflake's growth projections had significantly decelerated. The company predicted only a 24% growth rate for fiscal 2025, down from the previous year's 38%. This decline in growth prospects likely influenced Berkshire's decision to exit the investment.

Snowflake's increasing expenditures associated with investments in artificial intelligence (AI) were affecting its overall profitability. This shift away from Buffett's ideal of businesses requiring minimal capital while generating high returns likely contributed to the exit. In addition, the recent appointment of Sridhar Ramaswamy as CEO may have also played a role in Berkshire's decision. Combs' previous rapport with Frank Slootman could have been disrupted by this change, potentially affecting Berkshire's confidence in Snowflake's leadership.

Berkshire Hathaway sold its entire stake in Snowflake, approximately 6 million shares, in the second quarter of 2024. This move was part of a broader strategy to reduce exposure to high-growth but potentially volatile tech stocks and to reallocate capital towards more stable investments.

The decision to exit Snowflake aligns with Berkshire's focus on value investing and its preference for straightforward business models that require minimal additional capital to maintain competitiveness. Ulta Beauty, which Berkshire invested in shortly after exiting Snowflake, fits this criteria with its stable financial landscape and robust profits.

8. The Sin of Omission

Missing out on a fantastic investment opportunity because of fear or indecision can be as costly as making a bad investment. This mistake is illustrated in one of the oldest stories about a bubble market, when tulip prices skyrocketed due to expected high demand, leading investors to invest heavily in tulips, only to realize that they had been caught up in a speculative bubble and the demand was not as substantial as they had thought. We all could fall prey to this mindset, especially when it comes to investment opportunities associated with the term "AI". Do your own due diligence!

In 2011, Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway faced a controversy involving David Sokol, chairman of several Berkshire subsidiaries. Sokol recommended Lubrizol Corporation as a potential acquisition target without disclosing his personal stock ownership in the company. This violated Berkshire's insider trading rules. Berkshire proceeded with the acquisition for $9 billion, and Sokol profited about $3 million from the deal.

An internal investigation revealed that Sokol was evasive about how he acquired the Lubrizol stock, failing to mention that he purchased the shares after meeting with bankers who proposed the acquisition. Buffett eventually acknowledged the ethical breach but only after initially stating that no one was at fault.

This incident highlights that even experienced investors like Buffett can make mistakes. The key takeaway is the importance of due diligence and maintaining a healthy skepticism. Always have a checklist, follow a process, and ask as many questions as needed. When your reputation is at stake, thoroughness is crucial.